A George Town shop house feature: the interior airwell

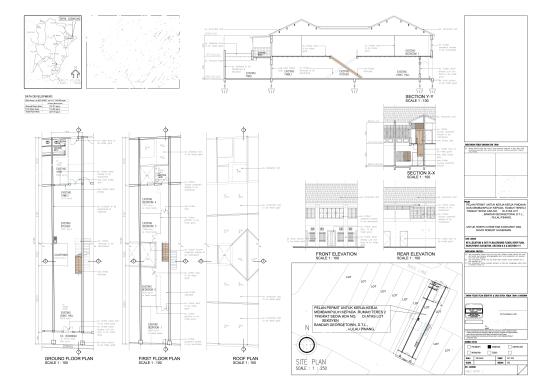

Our shop house, we think, is “Southern Chinese” Eclectic style, built between the 1840s and the 1890s. This is what we glean, anyway, by comparing our house’s facade to those pictured in this pamphlet put together by CHAT (Cultural Heritage Action Team), an organization of folks concerned to protect George Town’s tangible and intangible heritage.

Long before we ever imagined becoming homeowners here here we wandered the streets of George Town as tourists, admiring its lovely old shop houses and wondering what was behind their wooden doors and shutters. Now we know of course. You can too, in a way — the CHAT site has a great cutaway diagram of Penang shop house features that can be viewed here.

Shop houses are built attached, in rows (row houses is what they might be called elsewhere). Ours is a working class shop house, not nearly as large or as grand as the one pictured in the CHAT diagram. If you’re imagining Peranakan interiors — lots of gilt and dark wood — that is definately not our place.

But our house features some of the same elements, the most important of which is the interior airwell, a large rectangle in the center of the house, bordered by one wall, that’s cut from floor through the roof. It is this feature, more than any other, that endeared us to George Town’s shop houses. For us it’s an amazing thing to have the interior of your house open to the sky, to the elements, to air and to sun and to rain. Imagine having it rain inside your house. The airwell was designed to let in light and to aid ventilation and it is an amazing invention. Even without ceiling fans going the ground floor of our house remains fairly cool on sunny days. (This may also be because our house faces east so when we do get direct sun it’s at the coolest time of the day.)

These photos are for the most part from the very first time we viewed the shop house. We didn’t see it again until we were owners.

This first one is looking into the shop house through one of the front windows. The wooden shutters are intact. The former owners, a tailor and his wife, were still hard at work on the day we stopped in, but assured us that they were ready to retire.

This was important to us. At the time that we bought our house property in George Town was changing hands like crazy — a result, mostly, of the city having been designatd a Unesco world heritage site the year before. Many of GT’s houses are owned in bulk by family trusts or Chinese clan associations, and dividing into separate titles multiple properties originally listed together on one is time-consuming and costly. So in those days especially entire blocks of shop houses were being bought and sold at one go. Many long-time George Town residents are tenants, and so it wasn’t uncommon to see a swathe of shop houses cleared of occupants after a group of properties had changed hands.

We’re not making judgment call on buying property and evicting its tenants; it happens all the time in cities all over the world and is inevitable when urban areas undergo gentrification. It’s especially inevitable when a city becomes attractive as a potential tourist destination — making property more sought-after — as George Town did as soon as it was named a Unesco world heritage site in 2008.

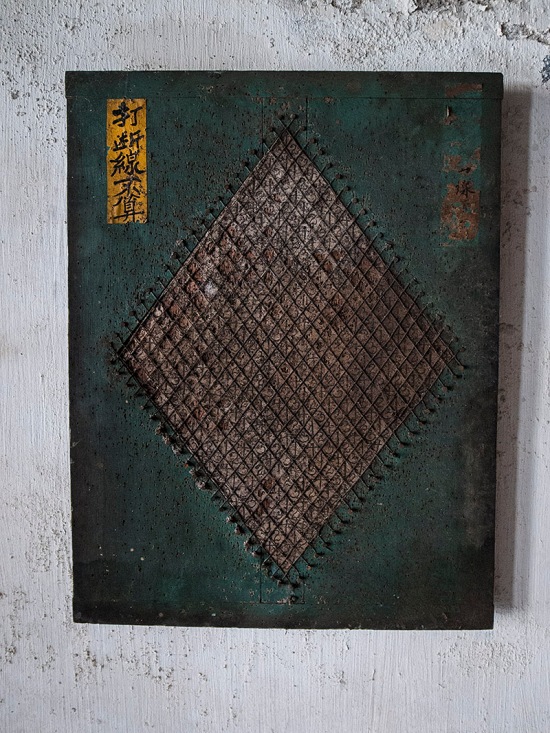

The tailor’s tools

We only knew that we ourselves could not bring ourselves to ask a long-term tenant to leave any property we bought, so we passed on those occupied by renters. Ah Tong Tailor felt OK to us not only because we liked the house but because the owners weren’t living there and were only using the building as a place of business (a very old business, to be sure). They said they were ready to leave. We very much hope that that was true.

This is a view from the house’s airwell looking out through the front windows. Our house is about 110 feet long and around 14 feet wide. The floor is cement, probably poured directly over original terra cotta tiles — which kind of kills us. We could try drilling through the cement to excavate the tiles but it would cost a fortune and the likelihood of saving them is very small. So we’re leaving the cement. It’s got its own mottled history.

In the photo below we’re looking from the airwell out in the opposite direction, to the back of the house. The wooden wall with the window isn’t a permanent structure. In many shop houses rooms are created on the ground floor by building those sort of wood-paneled “boxes”. They’re usually raised off the floor by a few inches. This one comprises two bedrooms, judging by the (unfortunately unsalvageable) furniture that we found inside.

The bit of blue tile on the left wall marks the indoor “kitchen” — there’s a sink there, and a burner and a teapot on the table in the middle of the room. The door in the back on the right leads to the courtyard, which is where the real kitchen would have been. Running along the wall opposite to the outhouse was an approximately 12 foot long rough cement bench where gas burners would have sat. In Malaysian and many other Asian homes “stinky” cooking was traditionally done out of doors. Even today most homes have a “wet kitchen”.

Now we’re in the small courtyard, which is is cemented over, looking at the rear outdoor wall of the house. The courtyard is enclosed by very high walls and will make a nice little private outdoor space. Just outside our courtyard in the alley is a small temple — built illegally obviously, because its wall is close enough to ours to make carrying building materials (or furniture, when we finally do move in) in and out through our door unfeasible. There’s enough space for us to get out in the event of a fire, and that’s what’s most important. We have no desire to anger any god or spirit by asking the temple’s builder to dismantle it.

This courtyard wall will look different when we’re finished with the refurbishment — a timber frame visible on the wall’s interior tells us that the original window was actually much larger.

But now I’m getting ahead of myself.

One thing not visible here: the downstairs “bathroom”. It’s actually an outhouse in the corner of the courtyard next to the exit out into the alley behind us. We plan to leave it there. And vastly upgrade it!

Now we’re upstairs looking down into the airwell.

Alas, we will have no rain inside our house. When the ground floor was cemented over the lovely granite well into which rain would fall was filled in. Our contractor reckons that the ground floor was built up with cement to deal with flooding during heavy storms. We considered excavating the well, but George Town has drainage issues that have yet to be addressed (though it’s been promised they will be). There’s no danger of rainwater rushing into our house via the front or back doors, but the thought of backwash through the drain in the interior well was enough to convince us to leave it cemented over.

There is however a semi-translucent retractable roof over our airwell, so we can open up the interior of the house during fine weather.

The wooden stairway tops out in the middle of the first floor, which is made of wood (much of which must be replaced). The ladder on the left leads up to a fairly roomy crawlspace — not high enough for either of us to stand in but probably roomy enough to have served as sleeping and/or storage quarters at one point.

This is a view out the back of the house. The door leads to a very rudimentary bathroom and there are two rooms on the left, one right behind the other. The airwell is also to the left.

Here we have another view of the upstairs hallway, standing behind the stairs and looking out to the front of the building. The airwell is on the right. This area was divided into three rooms, two side-by-side at the front and one behind, facing onto the airwell. The front rooms get fantastic light and the photographer has claimed this space for his office. We’ll have just two rooms here.

We love the rustic wooden latticework that tops the wooden walls; its common in shop houses like ours. The lattice lets light into the interior rooms that otherwise get light only from the airwell. We want to keep it but we need air-con for sleeping and for our offices. This is especially so for Dave, given his photo equipment and boxes and boxes of slides. The answer probably lies with glass or plexi panels over the lattice.

Below we’re standing in one of the front rooms looking out to the staircase. The original wooden double doors are still there and in good shape. All of the double wood doors upstairs in fact are useable, as is the heavy single timber door that leads out back to the upstairs bathroom.

On that first day we spent a lot of time upstairs looking at Ah Tong Tailor’s walls. Not at the blistered, moisture-seeping plaster or the termite-eaten boards, but at the evidence of all the years lived in that house.

Note: Yes, we’re playing with blog themes, trying to find a good balance between text and photos. We’re new to WordPress and finding this process rather tedious. Until we get it figured out, photos that appear small can usually be viewed larger just by clicking on.